HTXplains: Cracking cases with proteomics

Bet you didn’t know that the proteins in our bodies hold valuable clues that could help investigators identify perpetrators

By Janna Giam

Published on 3 December 2025

SCROLL DOWN

Photo: Canva

A violent crime has been committed. The scene has been scrubbed clean. There are no eyewitnesses, no usable fingerprints, and what’s left of any DNA has since degraded.

Sounds like the perpetrator will get away scot-free? Think again.

Thanks to proteomics, investigators might have another potential lead to pursue.

Proteomics refers to the large-scale study of proteins, particularly their structures, functions, interactions and quantities in a biological system.

While still in early stages, there is a possibility that advancements in proteomics could enable scientists to reliably identify an individual’s age, sex or ancestry through proteins in the future.

Not just sustenance for gym-goers.

Many of those who hit the gym regularly would likely know how important protein is when it comes to building muscles.

But proteins do far more than that. In fact, they also play a critical role in the formation of things like our bones and hair. Proteins also carry oxygen, digest food and fight infections.

Collectively, these complex molecules – which are made up of amino acid chains and synthesised based on instructions encoded in our DNA – are known as the human proteome.

Within the proteome, there can be up to a whopping 20,000 distinct proteins.

So, how are so many distinct proteins formed?

Imagine this: each cell in your body holds an identical copy of a giant cookbook. Think of this cookbook as your DNA. And in this book, there are 20,000 recipes that make different proteins. Why is there a need for so many types of proteins? Read on. (Photo: Pexels)

Our body is made up of different kinds of proteins. This means that when the body needs a structural protein to build or repair tissue, one needs to be specially created for such a purpose. The same goes for fighting off that nasty cold – the body creates an immune protein to get the job done. To create proteins, cells copy protein recipes from the book, as if writing it down on a notepad. (Photo: Pexels)

Referring to the recipe on the notepad, the exact amino acids that make up the protein are brought to the cooking pan in just the right amounts. (Photo: Pexels)

The amino acid ingredients are added to the cooking pan in the right order. (Video: Pexels)

And once all the ingredients are added, the chain of amino acids folds into a unique shape to form the completed dish, or in this case, the required protein! (Photo: Pexels)

While all the cells in your body may hold the same DNA cookbook, different sets of recipes are used across the various tissues, which results in several protein combinations. What this means is that certain proteins specifically belong to specific parts of the body.

And this specificity is precisely why proteins could provide leads in forensic investigations. In the absence of DNA evidence, the proteins specific to hair, skin or bones could be used to identify unique individuals.

In fact, proteins could also shed light on the health status of the individual, sequence of events, or the time since death, especially in situations where DNA analysis is not possible.

“Seeing” proteins Scientists already began analysing blood, urine, and other body fluids in the 1800s, building the foundations of protein science. (Photo: Google Gemini)

Scientists already began analysing blood, urine, and other body fluids in the 1800s, building the foundations of protein science. (Photo: Google Gemini)

So, how do scientists “see” proteins?

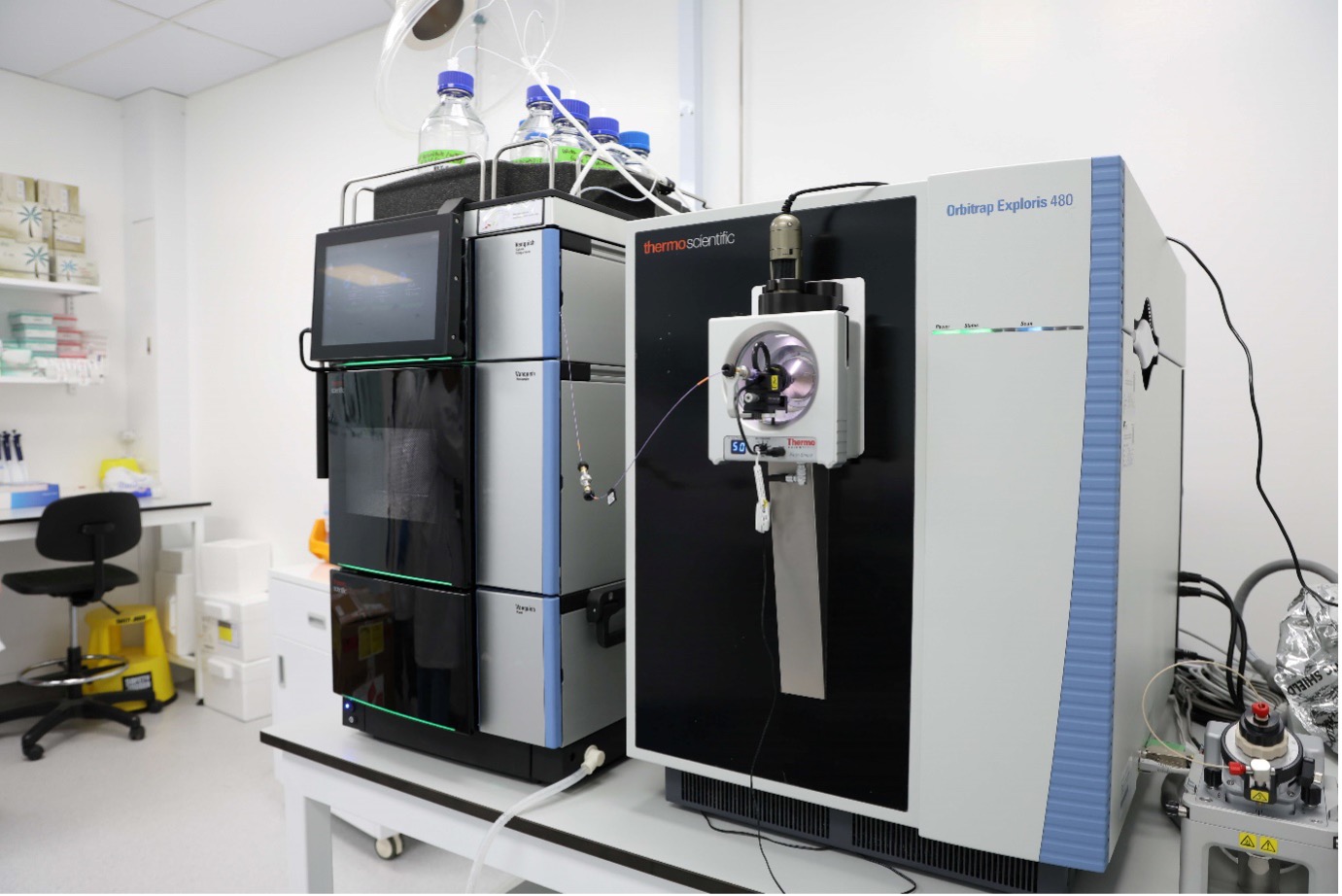

Mass spectrometry is one such method.

Think of a mass spectrometer as a state-of-the-art weighing scale for molecules. Not only is it able to detect trace amounts of substances, it also has high specificity, meaning it is able to distinguish between very similar molecules.

On top of that, its broad coverage means it is smart enough to detect a wide range of molecules and proteins.

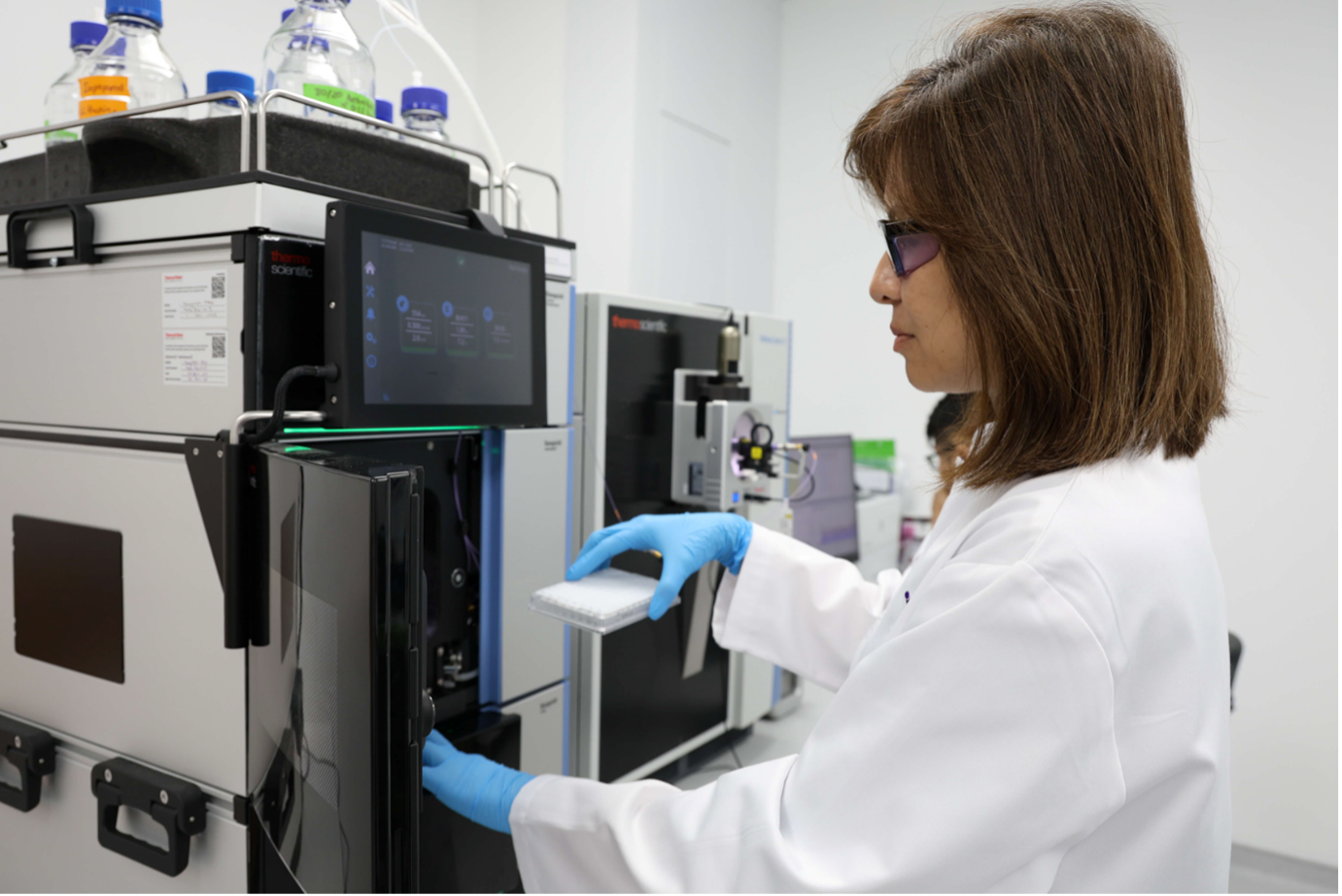

At HTX, the Forensic Innovation and Research for Strategic Transformation (FIRST) laboratory is fitted with a liquid chromatography system that is coupled to a high-resolution Orbitrap mass spectrometer, which research scientists from the agency’s Forensics Centre of Expertise (CoE) use to run analyses of proteins and their sequence variants to develop new investigation capabilities for the Home Team. The liquid chromotography system and mass spectrometer setup at HTX’s FIRST lab. (Photo: HTX/Janna Giam)

The liquid chromotography system and mass spectrometer setup at HTX’s FIRST lab. (Photo: HTX/Janna Giam)

From bodily fluids to skin and stomach contents, the team’s research goes deep into proteins from various biological materials.

One key area of focus? Hair proteins.

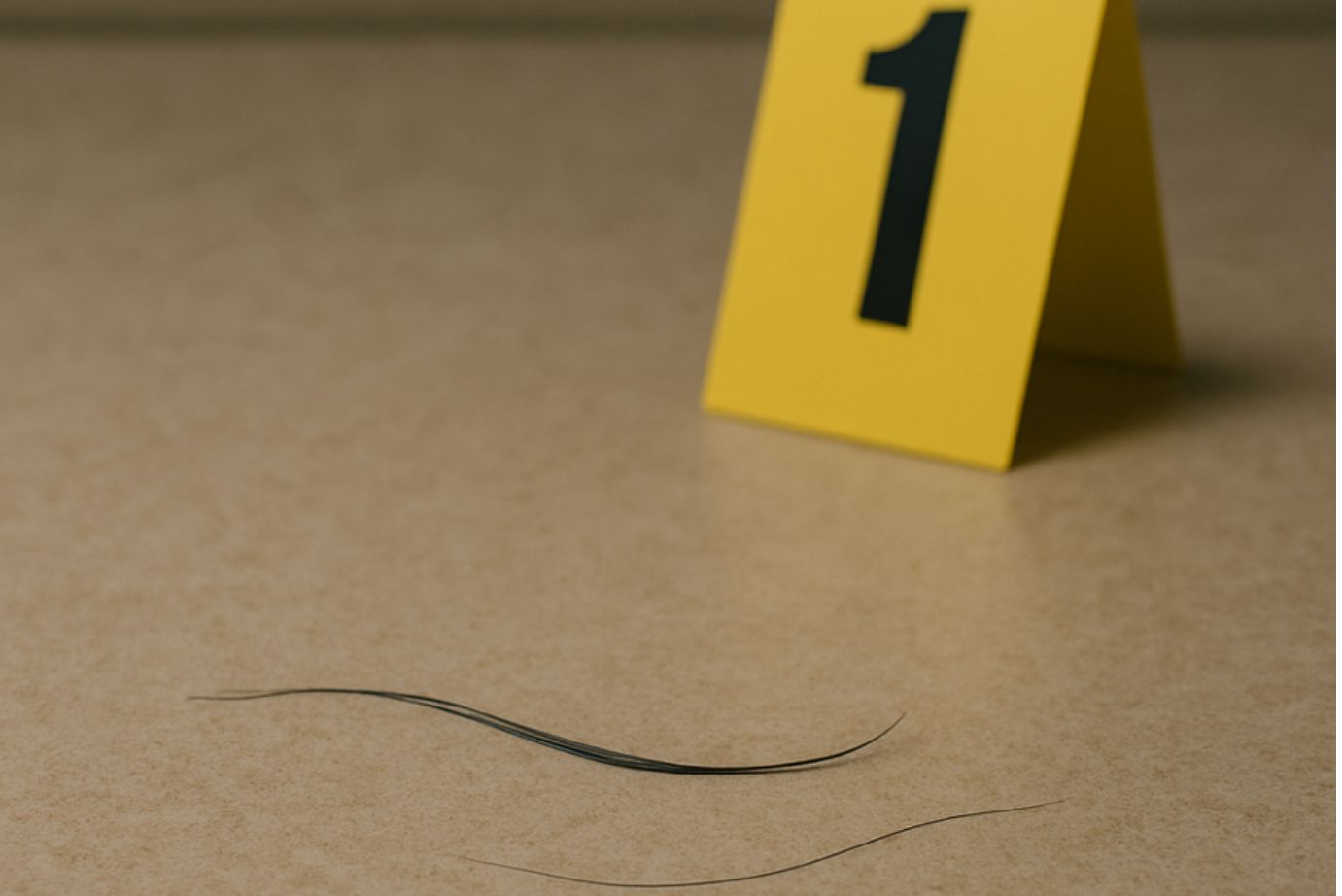

Did you know that an average person sheds about a hundred strands of hair each day? And that our hair carries protein sequences unique to us?

While shed hair typically does not contain enough intact nuclear DNA for short tandem repeats (STR) profiling – a DNA analysis method – it is loaded with keratin proteins, which makes it a goldmine for proteomics.

So, how exactly are hair proteins analysed in forensic investigations at the FIRST lab?

Firstly, a hair sample from the crime scene is obtained. So are hair samples or reference DNA from victims or suspects – so that a comparison can be made. (Photo: OpenAI)

To prepare for analysis, the samples are physically broken down into smaller pieces using a homogeniser…

…and chemically broken down from proteins to peptides.

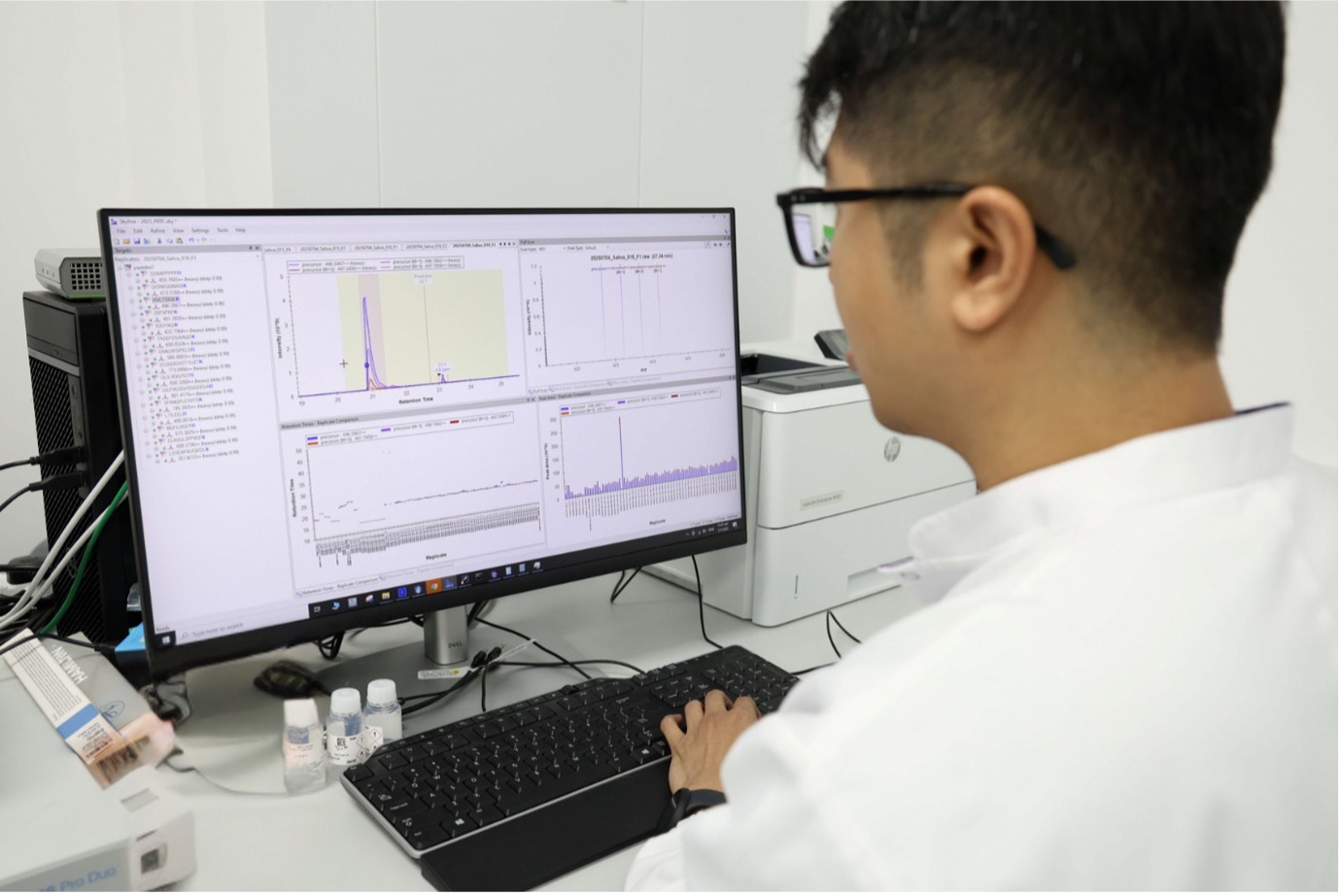

They are then run through the high-resolution liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry system.

When the results are out, the sequences of hair peptides are compared between the case and reference samples. (Photos: HTX/Janna Giam).

And if it’s a match, they’ve got their person of interest! (Photo: Freepik)

Deeper investigations

While proteomics can potentially provide crucial clues for forensic investigations, DNA profiling is still considered the gold standard.

Why? Because it is still an emerging technology. As such, there is a lack of standardisation of techniques used in labs around the world as well as a lack of complete and well-represented databases today.

That being said, proteomics could still enhance investigations by providing additional context to events that have transpired. And in cases where DNA has become degraded or unusable, or in situations where there is no DNA at all, proteomics could fill the gap.

Case in point? The case of a two-year-old's unnatural death in North Vancouver, Canada, back in 2014.

While bruises on the victim’s body first suggested some kind of blunt force trauma, further investigation using proteomics uncovered the presence of non-human proteins in the victim’s blood samples, which were later matched to proteins found in snake venom.

Paired with the knowledge that the child had been cared for by a family friend who kept venomous snakes, investigators were able to conclude that she died from a snake bite.

“With our work in proteomics, especially in the study of hair proteins, we aspire to assist the Singapore Police Force (SPF) in criminal investigations such as violent crime, abduction and missing person cases,” said Chen Liyan, a senior forensic scientist from HTX’s Forensics CoE.

“Proteomics is a powerful but under-utilised tool in forensic science. The team at FIRST is hopeful that our work will provide solutions for unmet needs, looking beyond existing methods of identifying individuals and unknowns.”

But the technique is not quite perfect yet. Right now, the team is able to identify persons at an estimated one in 50,000 level of precision, and they aim to enhance that to one in millions by optimising sample extraction, data acquisition and bioinformatics workflows.

“Moving forward, we plan to expand our study to include a more diverse recruitment pool that reflects Singapore’s multi-ethnic population. This would help to validate our workflow’s reliability in order to operationalise proteomics analysis for SPF’s case investigations,” explained Liyan.