First responders are exposed to greater risks from heat and physical load. (Photo: Freepik)

First responders are exposed to greater risks from heat and physical load. (Photo: Freepik)

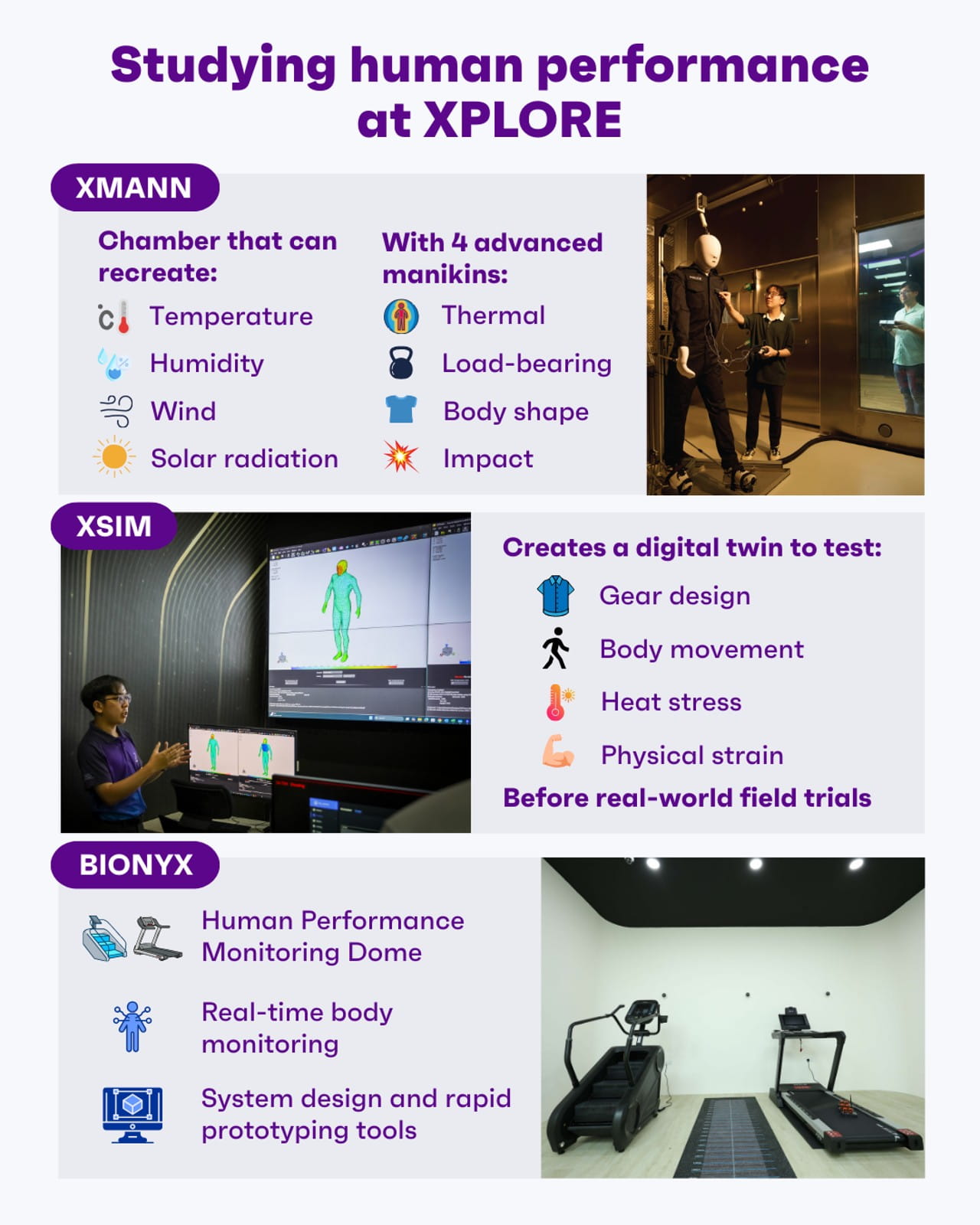

- At HTX’s XPLORE, scientists from the Human Factors & Simulation (HFS) Centre of Expertise (CoE) study how heat and physical load affect frontline officers’ safety and performance.

- Using tools like digital human twins, sensor-equipped manikins and simulation technology, HFS tests and refines gear, protocols and training before real-world deployment.

- Insights guide innovations such as cooling technologies, helping first responders operate safely under extreme conditions.

When was the last time you groused to a colleague that the steamy weather was sapping your energy and resolve to work, only to be derided for being melodramatic?

Having such discomfort casually dismissed may be harmless in an office, but out on the public safety frontlines, it can spell trouble.

To better understand how the human body performs under pressure, HTX launched XPLORE (Human Performance ModeLing and SimulatiOn REsearch Facility), the Home Team’s first-of-its-kind facility dedicated to modelling and enhancing both mind and body performance. The goal is to design safer, more effective systems, gear and environments for Home Team officers.

Here, in a futuristic facility kitted out with treadmills, manikins and Virtual Reality (VR) headsets, Dr Deng Rensheng, a Lead Scientist of Human-Environment Interaction at HTX’s Human Factors & Simulation (HFS) Centre of Expertise (CoE), examines how officers think and move under operational stress. His team then uses these insights to design simulations and scenarios that render training more realistic and sharpen decision-making in high-tempo situations.

Beyond training, Dr Deng studies how stressors such as heat and physical load affect the physiology (how the body responds and copes) and biomechanics (how the body moves) of frontline officers, and devises solutions to tackle those challenges.

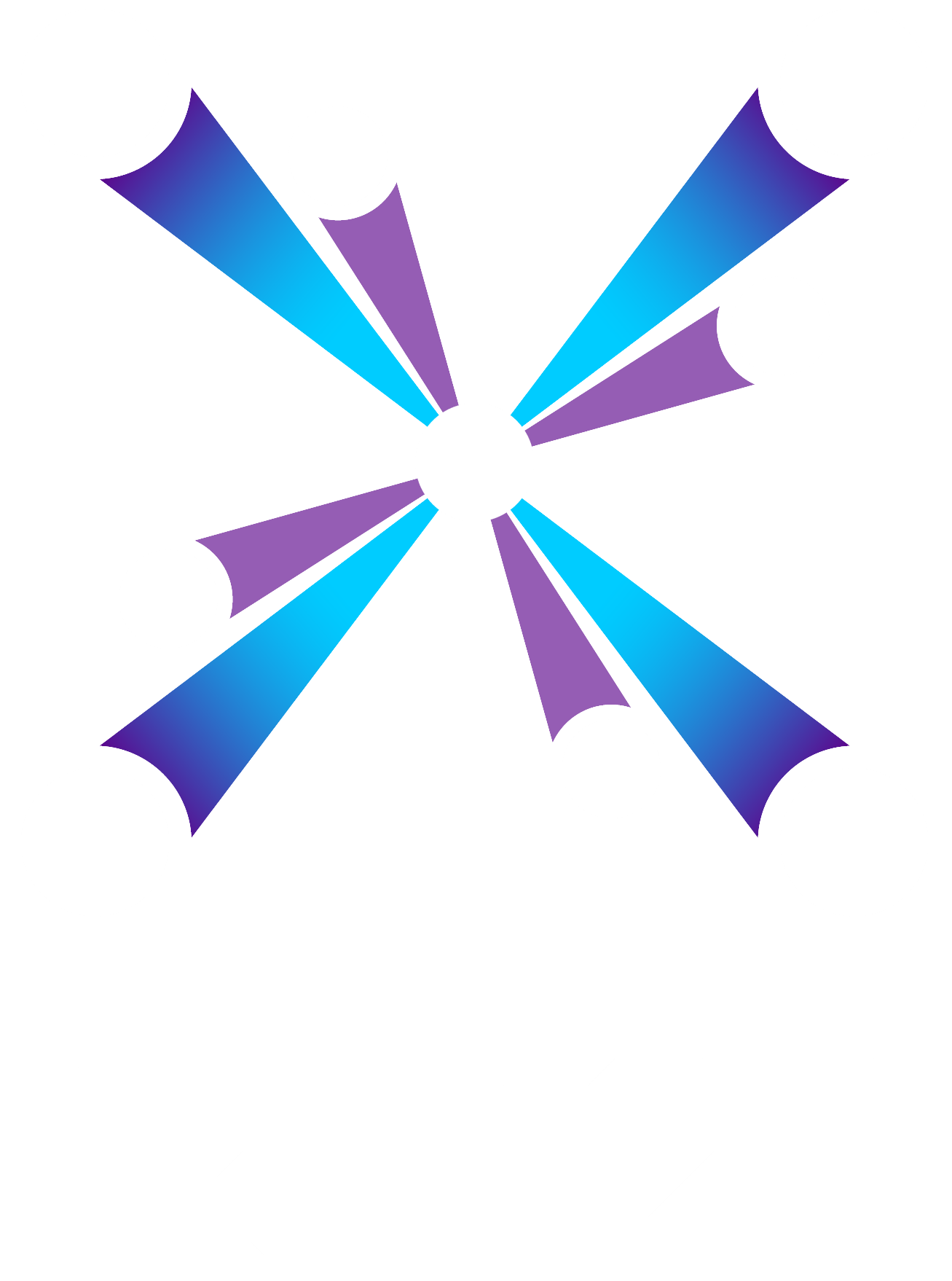

(Infographic: HTX/Nicole Lim)

(Infographic: HTX/Nicole Lim)

The scientist explained that the human body typically employs automatic physiological and behavioural processes to maintain stability and perform safely and effectively in the face of such stressors. For example, we don’t perspire simply because the weather’s hot – this physiological process is in fact the body’s way of dissipating heat through evaporation.

But there’s only so much the body can do to stay cool. When faced with extreme heat that overwhelms our compensatory mechanisms, our health or performance can be affected.

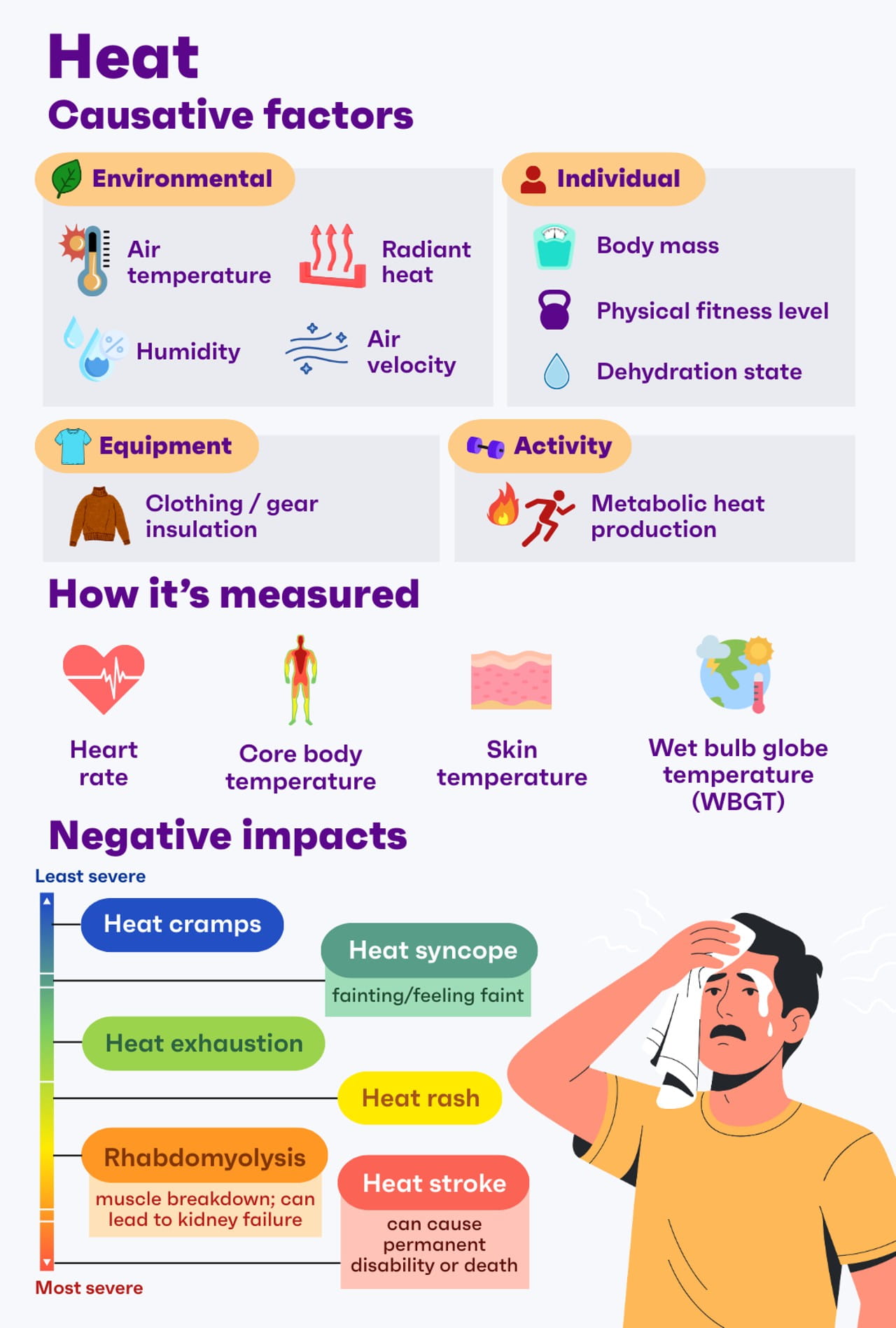

(Infographic: HTX/Nicole Lim)

(Infographic: HTX/Nicole Lim)

“Prolonged exposure to high heat or excessive load can lead to heat exhaustion, dehydration or cardiovascular strain, which may result in increased risk of injury or illness,” said Dr Deng.

What is heat exhaustion? Well, it’s the point at which the body struggles to regulate its internal temperature. You see, prolonged heat and physical exertion cause excessive sweating, and this leads to fluid and electrolyte loss. As dehydration sets in, blood volume drops and this forces the heart to work harder to maintain circulation. When less blood reaches the brain and muscles, symptoms such as dizziness, confusion, slowed reaction times and muscle weakness start to kick in.

If left unaddressed, heat exhaustion can escalate into heat stroke, a life-threatening condition where the body’s cooling mechanisms fail entirely.

High stakes under high strain

While the effects of heat and physical load may not always send someone to the Emergency Room, they can prove dangerous in professions with mounting cognitive and physical demands – such as operating in harsh environments intensified by climate change.

Scientists at XPLORE evaluate how Home Team officers perform in realistic environments. (Photo: HTX/Law Yong Wei)

Scientists at XPLORE evaluate how Home Team officers perform in realistic environments. (Photo: HTX/Law Yong Wei)

Dr Deng highlighted that frontline officers face far greater risks from heat and load than the general population because their jobs expose them to both factors at the same time. This is compounded by their relative lack of control over when and how these stressors occur, plus the demands placed on them to maintain high performance.

“Firefighting does not constitute steady-state exercise; rather, it involves unpredictable and intense bouts of activity. Stress hormones can alter perceptions of heat and fatigue, and errors made under such challenging conditions may have serious, even life-threatening consequences,” he cautioned.

Picture a high-octane situation in flux: First responders are unable to pause, rest or reduce their pace until the incident is fully managed – despite experiencing physiological stressors such as elevated heart rate and increased core temperature.

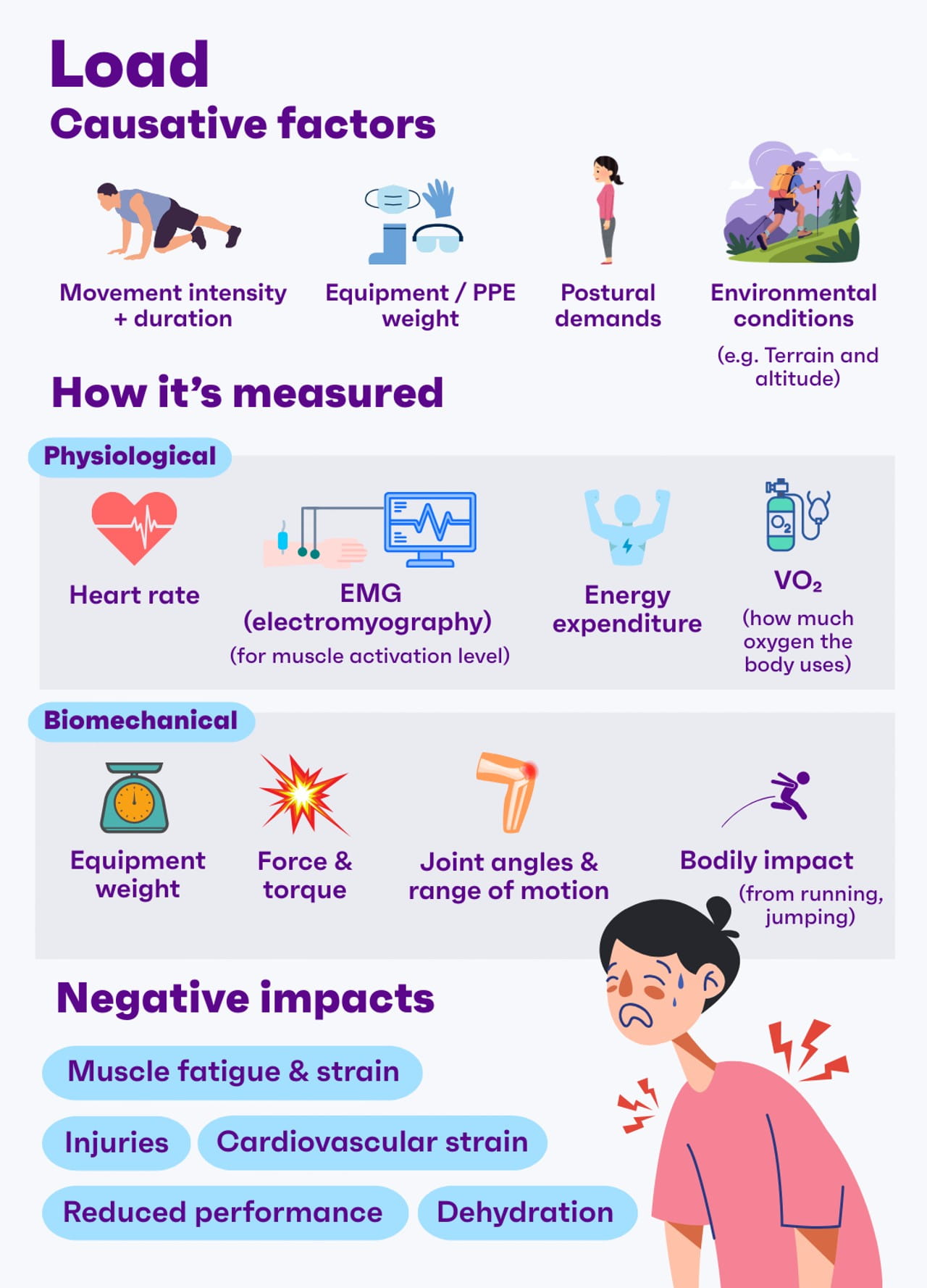

(Infographic: HTX/Nicole Lim)

(Infographic: HTX/Nicole Lim)

That said, the way first responders cope with physical and cognitive demands can vary dramatically.

“This is because experience builds movement efficiency, energy discipline and psychological tolerance to discomfort,” explained Dr Deng.

For example, experienced officers can handle load more efficiently by distributing their weight better, moving with less wasted muscle effort and intuitively adapting their stance. Hence, it is crucial to evaluate individual capacity in a controlled environment to bolster safety and performance.

XPLORE: Ensuring first responders’ safety and performance

Dr Deng Rensheng (left) with Minister of State, Ministry of Home Affairs and Ministry of Social and Family Development Mr Goh Pei Ming, at the launch of XPLORE. (Photo: HTX/Nicole Lim)

Dr Deng Rensheng (left) with Minister of State, Ministry of Home Affairs and Ministry of Social and Family Development Mr Goh Pei Ming, at the launch of XPLORE. (Photo: HTX/Nicole Lim)

To help the Home Team stay ahead of these challenges, Dr Deng and his teammates work toward designing safer, more effective systems (training and operational procedures), gear and workplaces at XPLORE.

Across its specialised laboratories, tools are harnessed to predict how officers’ bodies respond to factors like rising core temperature (the body’s internal heat level) or heavy equipment load. Among these tools are digital twins – virtual replicas of a person’s body created through body scans and simulation software – as well as life-sized, sensor-equipped manikins that mimic human bodies.

According to Dr Deng, digital and physical models yield unbiased results in repeated experiments due to their consistency as test subjects.

“In contrast, human participants exhibit variability influenced by factors such as weather, time of day, mood, diet and other conditions, potentially affecting experimental outcomes,” he explained.

Subsequently, the researchers can test and prototype new gear or protocols, validating each iteration using physical models as well as human subjects.

For example, at the BIONYX Lab, human participants equipped with body-augmentation systems are directed to perform movements related to their operational tasks. Sensors track how their bodies move and respond, helping researchers understand what works well, what causes strain, and how tools, gear and workflows can be improved.

(Infographic: HTX/Nicole Lim)

(Infographic: HTX/Nicole Lim)

While XPLORE was recently launched, several innovative projects are already underway. For example, Dr Deng and his teammates are developing new cooling tools to help first responders recover faster from heat stress – such as a bench that uses electric currents to create a chilled surface that draws heat away.

Looking ahead, Dr Deng predicted that the increasing frequency and severity of extreme heat events is evolving heat stress from a niche occupational concern into a wide-ranging issue affecting worker health, national productivity and overall safety. In response, global guidelines are shifting to reflect real-world conditions.

At HTX’s HFS CoE, this shift takes the form of a worker-centric, human-centred approach that prioritises personalised monitoring and adaptive prevention. Drawing on evidence-based modelling, simulation, field validation and emerging technologies such as Internet of Thing (IoT) sensors, VR/AR, AI and machine learning, HFS is helping to refine training protocols, update work-rest cycles, redesign equipment and deepen understanding of how heat and load interact to affect frontliner performance.

“Protecting our frontliners begins with understanding the person, not just the problem,” concluded Dr Deng.